The Great Blue Hill trail map, courtesy of MassAudubon.

The noise has been getting to me.

It started last month, spending so much time in Downtown Crossing. My days down there were mostly spent hanging balsam wreaths and setting out other Christmas decorations. The sound there is endless, all engines and heavy gaits and voices. It’s not the nicest part of Boston; there’s a lot of misery and a lot of seediness. At first I took pleasure in bringing green to the grey, planting spruces and spring bulbs, reaching the bowed wreaths up ladders. But as December darkened the noise grew too heavy to bear.

Nearly everything else in my life is quieter and less crowded, but that sound has stayed with me—the drone and the colors. And the shapes of humans, sometimes hardly anything but a harsh shadow. There are a lot of shelters, a lot of drained eyes, a lot of bedrooms made of cardboard.

That is hard living and, guiltily, I’ve shirked away from it. I’ve only been downtown twice since the holiday madness ended and was struck by the darkness, the crammed decibels. I’ve been longing for spaces, for long ones humming gently in human-free life. I’ve longed for the companionship of trees, of plants not so tame as to live in buildings, or so dead that they’re twisted into a wreath and hung to dry.

Yeah, well. The city is where I am. It takes more than a song to get out of here, especially on a Friday when rush hour starts early. And I’ve had work to do, words to write and spreadsheets to create. I’ve felt crazed with restlessness. The memory of sounds, the misery of stillness.

So finally I escaped to the Blue Hills.

I’ve written about that edge of town majesty elsewhere but, strangely, not here. It is a refuge to which I go in order to escape myself and find myself in turns. It is to me what the ocean is to Ishmael:

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping to the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

To sea for him, to trees for me.

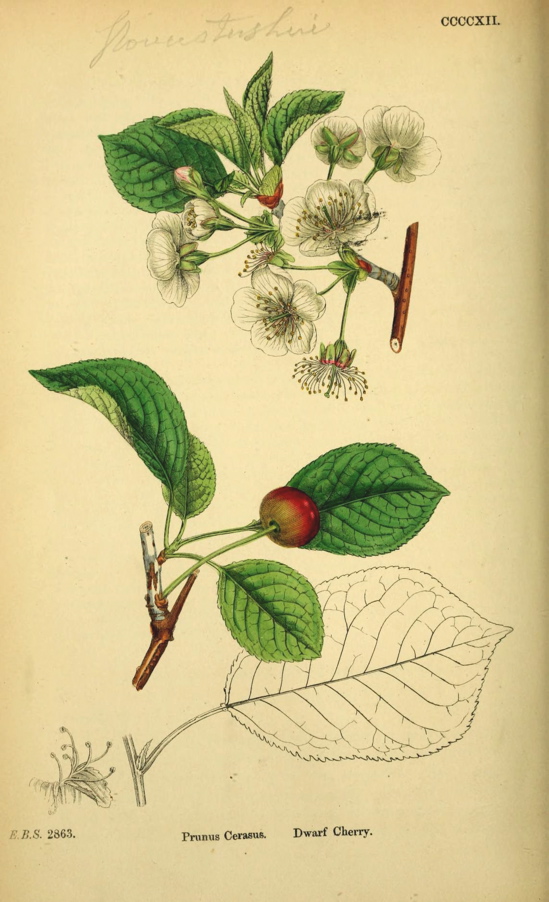

I parked at the Great Blue Hill, which rises alongside I-93 in pines,oaks, maples, and ski trails, and began climbing the road to the weather observatory. It had snowed all morning and the trees and forest floor were white, but my soul still felt pretty bleak. 128 runs right along the hill and the noise of it moved right up the road—fuzzy mufflers, rasping engines, heavy tires, the occasional pitch of a horn. The drivers below were hurtling along in their aluminum cans, heading home and picking up kids, and doing so Loudly.

Eventually I came to a path that rose into the woods, veering from the paving with steps made of the sort of perfect logs that build a cabin. Hungering for the uneven embrace of the earth I left the asphalt and carefully ascended the logs. They were slippery with the sneaky ice that lives in shadowy places and I took my time, feeling a tender rush of accomplishment after stepping off the last stair.

(Here I must admit that I pictured myself as Reese Witherspoon during this little hike, meaning that I pretended that this was a Very Great Journey instead of, um, an hour’s jaunt. So there I was, Hauf as Witherspoon as Cheryl strayed, grunting and humming in satisfaction, not wearing hiking boots or a pack, but feeling satisfied.)

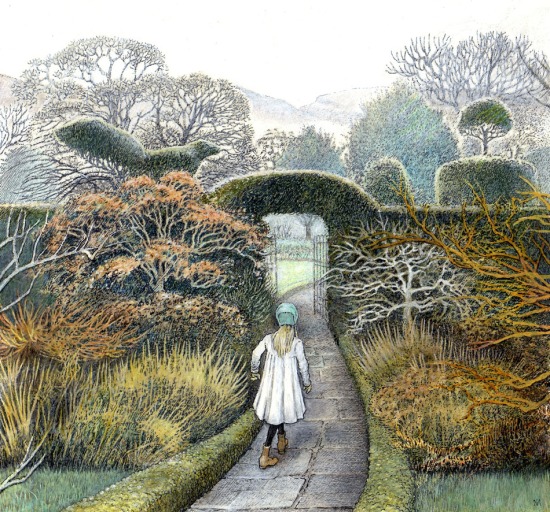

The path was close with branches and trunks and I walked, surrounded by life. The nearness of it eased me as I carried on up the red dot path and on to the blue dot, feeling a communion with the sweet green colors carrying nourishment below all the rough creases of bark around me. As I often do in the woods or gardens of winter I remembered Dickon in “The Secret Garden:”

“There’s lots o’ dead wood as ought to be cut out,” he said. “An’ there’s a lot o’ old wood, but it made some new last year. This here’s a new bit,” and he touched a shoot which looked brownish green instead of hard, dry gray. Mary touched it herself in an eager, reverent way.

“That one?” she said. “Is that one quite alive quite?”

Dickon curved his wide smiling mouth.

“It’s as wick as you or me,” he said; and Mary remembered that Martha had told her that “wick” meant “alive” or “lively.”

“I’m glad it’s wick!” she cried out in her whisper. “I want them all to be wick. Let us go round the garden and count how many wick ones there are.”

I didn’t count all the wick ones in the reservation, I just walked among the ones skirting my path. A quiet joy was spreading within me. I felt like I was strolling in the light of candles, ones that weren’t fussy and blown out by a breeze. I felt like a candle, glowing and warm.

Eventually I came to the old building with a roof and two walls for picnicking. From there it was a short tripto the hill’s summit. When I arrived at the top I moaned a long, honest, appreciative Ohhh of appreciation for the haze below and beyond, for the hills and valleys and forests dressed in the lovely grey blue. All of it blended together perfectly, all those colors of New England that have lived here for centuries.

As I went back down the hill, more patient now with paving, the snow filtered from the canopy like gilded motes, shining in the slanting sunlight. I walked in bliss and, when the traffic again began licking at my ears, kept on going. I had to join it, to go back home, to get to work.

This post is devoted to sauntering, a rare art espoused by Henry David Thoreau which I have resolved to embrace in this still new year. Saunter posts will hearby be tagged Saunterday, so keep an eye out for them!

From The Secret Garden.